An indictment accusing officials from the opposition-run Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality of wide-ranging corruption and bribery contains serious evidentiary gaps, according to an analysis of the court filing. Critics say the document relies on contradictory or uncorroborated statements, secret witness testimony and lacks clear proof of illicit financial transactions.

|

| Turkey: İmamoğlu case faces scrutiny over lack of evidence Turkey: İmamoğlu case faces scrutiny over lack of evidence Turkey: İmamoğlu case faces scrutiny over lack of evidence |

The historic case, which has led to the arrest of hundreds of officials from local governments run by Turkey’s main opposition party, the Republican People’s Party (CHP), is now under scrutiny over a lack of evidence, inconsistent handling of testimony and factual errors.

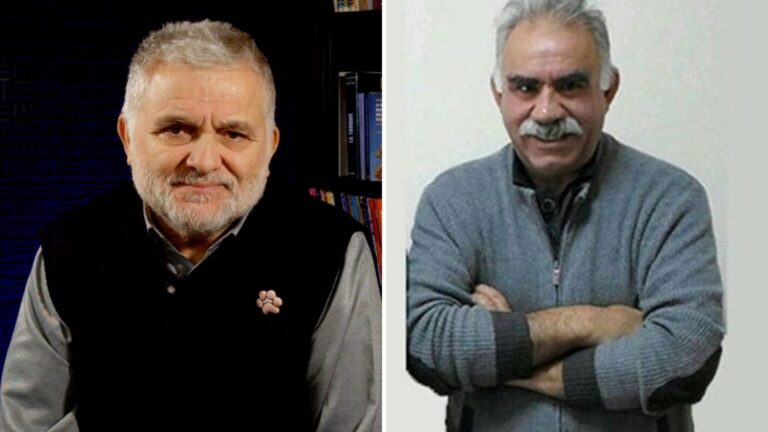

The investigation has seen a dozen-plus CHP mayors detained or arrested in related probes and has also led to the jailing of the party’s presidential candidate, Ekrem İmamoğlu — widely regarded as the most serious potential challenger to President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan or his preferred successor in the 2028 election. From the outset, opposition figures have described the case as a politically motivated attempt to sideline a rival.

İmamoğlu is a senior figure in the CHP. He rose to national prominence after winning the Istanbul mayoralty in 2019 and was re-elected in 2024, before later being named the party’s presidential candidate for 2028 — positioning him as one of President Erdoğan’s leading political challengers.

The indictment — nearly 3,800 pages long — portrays an alleged “İmamoğlu-led organised crime group” and links the defendants to a range of serious accusations, including bribery, fraud against public institutions and the rigging of public tenders. Prosecutors have described the alleged network as controlling municipal contracts “like an octopus”, echoing metaphorical language previously used by President Erdoğan to describe corruption networks.

Weak evidence behind bribery counts, analysts say

Despite its length and breadth, the indictment contains multiple bribery allegations that appear to rest on poorly supported testimony rather than documented evidence of illicit conduct.

No evidence of cash exchange

In one key episode, prosecutors allege that businessman Avni Çelik was pressured to pay a bribe in connection with a city-funded restoration project. In his statement to investigators, however, Çelik said the project proceeded normally, was worth about €3.5–4 million, and that no bribe was ever requested or paid. Despite this, prosecutors interpreted the interaction as a demand for a $3 million bribe, even misreporting the amount in the indictment.

Contradictory statements treated as evidence

In another count, a cooperating witness claimed a request of $500,000–$600,000 had been made. A second witness directly contradicted this, saying no such conversation took place and no restoration work occurred. Rather than resolving these contradictions, prosecutors treated the lack of agreement itself as evidence of bribery.

Denial taken as proof of guilt

In several sections, individuals who denied that any bribe was offered or accepted were nonetheless charged with bribery on the grounds that they refused to cooperate or accept a supposed offer. Critics argue this reverses basic assumptions about proof and undermines fairness in criminal proceedings.

Use of secret, uncorroborated testimonies

Some bribery and bid-rigging allegations hinge almost entirely on anonymous (“secret”) witness testimony, with no independent documentation or corroborating evidence. In one instance, the indictment cites unidentified witnesses claiming to have seen lists or discussions about contracts, without providing verifiable proof of wrongdoing.

Elsewhere, routine municipal activities — such as minor procurement decisions or informal remarks about competitiveness — are treated as evidence of criminal behavior, despite the absence of clear procedural violations.

Previous reports of multiple detainees alleging they were coerced into giving false testimony in exchange for their release have led to further scrutiny over the legitimacy of the government’s case.

With the first hearing set for March 2026, defence lawyers and independent legal analysts are expected to challenge many of the indictment’s weakly supported charges. Whether the court allows these counts to stand — or finds they fail to meet basic evidentiary standards — could prove a defining moment for both Türkiye’s legal system and its already polarised political landscape.

Original story by Furkan Karabay

Translated by Medyascope English Newsroom