On Monday (March 6), Turkey’s groups of six political parties that make up the “Table of Six” electoral alliance announced at an event in Ankara that Republican People’s Party (CHP) Chairman Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu had been selected as the group’s joint candidate to challenge President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in the elections expected to be held in May. The agreement came after a weekend of drama within the opposition in which İYİ Party head Meral Akşener briefly left the alliance after failing to agree with the other five parties on Kılıçdaroğlu as the joint candidate. Leading the second largest party in the alliance after the CHP, the İYİ Party Chairwoman had requested that the popular CHP mayors of İstanbul and Ankara be nominated in Kılıçdaroğlu’s place. Following an emergency meeting on Monday in which the two mayors agreed to serve as Kılıçdaroğlu’s vice presidents in the event of an opposition victory, Akşener and the İYİ Party rejoined the alliance and the CHP head was announced as the joint candidate.

Kılıçdaroğlu enters the candidacy as a long-time bureaucrat and adversary of President Erdoğan. The CHP head hails from the Tunceli district in eastern Anatolia, an area famed for its leftist leanings and heavily minority-dominated demographic make-up. Kılıçdaroğlu himself comes from an Alevi family, one of the area’s main minority groups. He rarely emphasizes this aspect of his background publicly, however Turkey’s Alevi community is traditionally heavily supportive of the CHP, Turkey’s founding father Atatürk, and secularism, all of which make up important pieces of Kılıödaroğlu’s political brand.

The candidacy announcement that unfolded in Ankara on Monday evening was notable among many reasons for the manner in which it displayed the opposition’s pluralistic make-up. The host of the event, the far-right Islamist Saadet Party, is headed by Temel Karamolaoğlu, a veteran Turkish politician who served as the mayor of the eastern Anatolian city of Sivas during a massacre in the city in 1993 which targeted and killed numerous Turkish Alevi citizens. Akşener herself is a longtime nationalist politician who was formerly a member of Erdoğan’s current coalition partner, the Nationalist Action Party (MHP), before a schism led to her departure in 2017 after which she founded the İYİ Party, intended as a MHP alternative for right-leaning nationalist voters in Turkey. Two other Table of Six members, Ahmet Davutoğlu and Ali Babacan, were former high-ranking officials in previous Erdoğan administrations who have gone on to form their own parties. As such, the spectacle outside the Saadet Party headquarters in Ankara on Monday night featured a unity of disparate factions that in most previous eras would have been politically untenable. While Kılıçdaroğlu’s victory is far from certain, the unity of the opposition in toppling Turkey’s 20-year strongman has reached a level never before seen during the Erdoğan era.

A graduate of Gazi University in Ankara, Kılıçdaroğlu worked his way up the Turkish bureaucracy throughout the 1990s when he worked for the country’s social security institution (SSK), eventually becoming director in 1994. Kılıçdaroğlu’s tenure with the institution has been a frequent target of criticism from President Erdoğan and other Justice and Development Party (AKP) officials; at various points the president has criticised how Turkey’s retirement age increased during Kılıçdaroğlu’s SSK tenure and how institution allegedly went belly-up under his watch.

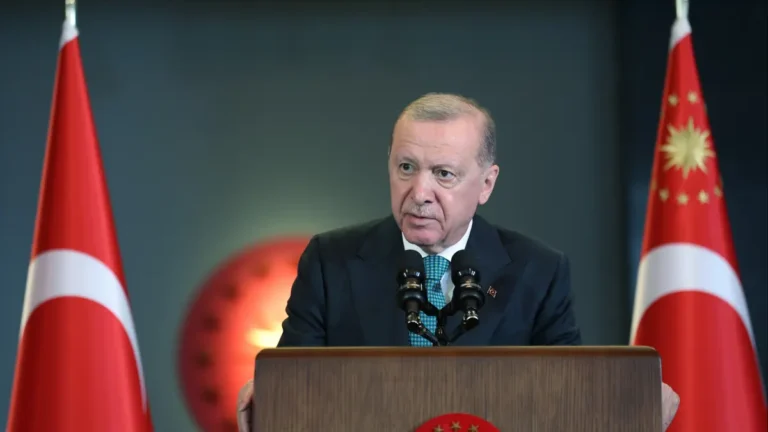

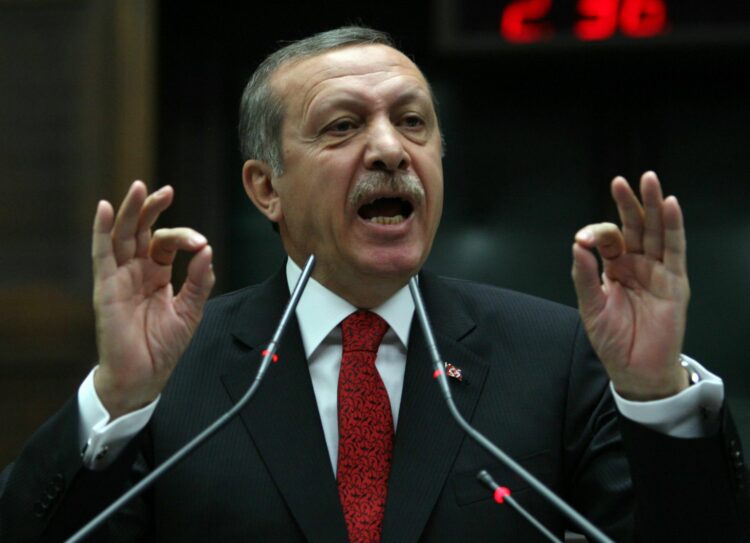

Erdogan in his own way demeans Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu by often calling him “Bay Kemal.” Roughly equivalent to “Mister” in English, the moniker “Bay” replaced indigenous titles like “Bey” and “Efendi,” used in the traditional Ottoman-Turkish parlance. Used in the Western fashion as a prefix, Bay Kemal implied from Erdogan’s point of view that Kılıçdaroğlu represented the Westernized and secular Turkey and portrayed him out of touch with the mainstream’s nationalistic, patriotic, and conservative values.

Kılıçdaroğlu’s reputation as an institutionalist and career bureaucrat may be in fact an upside for many Turkish voters this spring. The government’s failure to respond quickly to the devastation following last month’s earthquakes in southeastern Anatolia had many blaming the AKP’s top-down power structure and hollowing out of state institutions that has occurred under Erdoğan’s tenure. Search and rescue work following the quake, for example, was only allowed to be coordinated through the AFAD, Turkey’s disaster relief agency, which critics said hindered a more multifaceted disaster response. The limited involvement of the Turkish military in search and rescue efforts despite a breadth of resources was also frustrating to many and widely attributed to Erdoğan’s aversion to empowering the country’s armed forces, with which the president has long been gun-shy, in particular since the failed coup attempt in 2016. Thus, Kılıçdaroğlu’s bureaucrat resume may actually be welcomed by voters fed up with the weakening of Turkish institutions and centralization of power under the AKP.

As leader of the center-left CHP, Kılıçdaroğlu has also for years taken the role of a firebrand in opposing the oligarchy, corruption, and favoritism that has developed during the AKP years. One of the CHP head’s favorite targets is the so-called ‘Gang of Five’, a group of five holding conglomerates close to President Erdoğan’s inner circle who are frequently awarded Turkey’s largest and most lucrative construction tenders. Kılıçdaroğlu has promised to bring the ‘Gang’ to justice should he take the reins of power, and much of his political rhetoric has been filled with similar promises to disassemble the network of beneficiaries built up through years of alleged AKP favoritism.

Aside from his reputation as a bureaucrat, Kılıçdaroğlu also enjoys the unfortunate reputation as a loser among many Turkish voters. Since taking the helm at the CHP in 2010, the chairman has seen a number of defeats throughout his tenure including a failure to defeat the 2017 constitutional referendum which dictated Turkey’s shift from a parliamentary to presidential system that consolidated Erdoğan’s power, as well as the subsequent 2018 presidential election which the president won handily against a CHP candidate supported by Kılıçdaroğlu.

In 2019, Kılıçdaroğlu saw likely the biggest success of his political career when CHP candidates Ekrem İmamoğlu and Mansur Yavaş won municipal elections in İstanbul and Ankara, becoming mayors of both cities and delivering Erdoğan his largest political blow to date. The CHP’s success in these polls was due in large part to an alliance brokered by Kılıçdaroğlu that included Akşener’s İYİ Party as well as a host of smaller parties, cementing his reputation as a coalition builder. The fragile electoral alliance that resulted in Kılıçdaroğlu’s candidacy announcement on Monday can be seen as a direct continuation of the coalition which Kılıçdaroğlu led to success in the 2019 contests.

Another theme in Kılıçdaroğlu’s political rhetoric of late have been his calls for reconciliation amongst the Turkish public related to the country’s various historical wrongdoings towards certain groups. Known in Turkish as ‘helalleşme’, Kılıçdaroğlu’s calls for amends aim to heal wounds related to such topics as civil unrest and injustices in Turkey’s heavily-Kurdish southeast, attacks on various ethnic groups including Greeks and Alevis, the numerous coup d’etats throughout modern Turkish history, and more. Aimed in part at mending Turkey’s deep polarization, Kılıçdaroğlu has attempted to bill himself as a healer and uniting force in a deeply divided country through his helalleşme overtures.

Kılıçdaroğlu’s attempts at big-tent building and reconciliation are not without their pit-falls across Turkey’s diverse electorate. Although not part of the Table of Six coalition, the pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP) has recently shown an openness to supporting Kılıçdaroğlu’s candidacy instead of running their own, as they had previously announced. While the inclusion of a large number of Kurdish voters under Kılıçdaroğlu’s umbrella would win him some votes, such a move risks alienating the right-leaning nationalist voters that the alliance has worked hard to maintain under their wing. Akşener has gone as far as to rule out the notion completely, saying “The CHP cannot bring the HDP into our table.” Indeed, the HDP is bitterly disliked by many nationalist elements of the Turkish electorate, including Erdoğan’s coalition partner Devlet Bahçeli and his MHP party, and the leftist party currently faces a terrorism-related closure suit by Turkey’s constitutional court that is as yet unresolved. As Kılıçdaroğlu’s presidential campaign gains momentum, the role of this controversial yet sizable piece of the Turkish constituency is sure to be a topic of preoccupation for the CHP leader.

The CHP leader- turned- presidential candidate faces a political nemesis in many ways his opposite. President Erdoğan is a populist and strongman who for many years enjoyed the reputation of political invincibility. Kılıçdaroğlu, a career bureaucrat seen by some as dull and politically unsuccessful, has launched his campaign with the promise to revive Turkish democracy and resuscitate the country’s anemic institutions. In an era in which many voters’ desire to unseat Erdoğan is fiercer and more united than ever, Kılıçdaroğlu’s skills as a coalition builder faces its biggest test yet with the CHP head himself sitting at the top of the ticket.

Written by Leo Kendrick for Medyacope